Church Song

1. The early churches

1. GENERAL

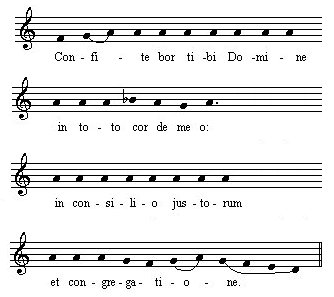

"Psalmody" refers to singing of psalms in the way David sang them: with accompaniment of his harp. Within the Gregorian style of singing, "psalmody" was important. This style of singing means reciting a psalm in the Latin language and text on one tone (tenor). The singing starts with an opening (initium), and has at the end of the line a middle cadenza (mediato), while the psalm is closed with a closing (terminatio). As an example Psalm 111 ("I will extol the LORD with all my heart, in the council of the upright and in the assembly.)

This way of singing the Psalms has gained renewed attention in the last 30 years, and many composers around the world have contributed an addition to the collection in Latin. They wrote new music for the psalms in many contemporary languages.

2. STRUCTURE

The structure of the recitative is built up of two parts, based on the Hebrew structure of the songs. The two parts are basically expressing the same thought; the two parts are complimentary, or are in contrast to each other. For example:

"He will cover you with his feathers,

and under his wings you will find refuge"

Psalm 91: 4

"How great are your works, O LORD,

how profound your thoughts!"

Psalm 92: 5"For the LORD watches over the way of the righteous, but the way of the wicked will perish."

Psalm 1: 6

3. OLD TESTAMENT

The history of singing in the Old Testament does not relate back to the temple (worship) service of Solomon. From the Talmud we know that one century after the devastation of the temple of Solomon (599 before Christ), the Israelites did no longer know the original performance of the psalms. The later practice in the synagogue had also some parallels with the practices of other nations around Israel at that time.

4. PRACTICAL

Since the 2nd century cantors we used in the worship service, taking care of the musical service in the church. The starting point for this musical service was based on the liturgy in the synagogue, which had several options of singing psalms:

- the cantor sings the entire psalm by himself

Here the congregation responds normally with "acclamations"

- the cantor and the group/choir alternate

- two groups/choirs sing alternatingly

Here the psalm is introduced and closed with the singing of a "choir", sung by the both groups together, while referring to the essence of the psalm.

The early church developed and practised the singing of psalms. During the first centuries many monasteries were also very active in this development. Is was quite common in the various monasteries to sing on a weekly basis all 150 psalms (Benedictines and Trappists). Some psalms were sung daily (4 and 90). For fifteen centuries the psalms were daily spiritual food in monasteries.

Melodies, music and regulations were in the 9th century for the first time structured and formulated, which again was a basis for the modes on which the Genevan tunes are based.

The further development of this manner of singing psalms, which was practiced in the Roman Catholic Church and many monasteries, is very worthwhile to pay attention to, also because of the rich musical and textual development and maturity today. However, this subject falls outside the scope of this project.

2. The Early Ages and Middle Ages

1. In the New Testament we read about "speaking to one another with psalms, hymns and spiritual songs". This is assumed to refer to congregational singing. Correct or not, it is a fact that the early church was accustomed to congregational singing (in 112 A.D. Governor Plinius writes to Emperor Trajanus about this, also we read in Ambrosius' (340-297 A.D.) letters about the singing of the church).

2. In the 4th Century Christianity became the state religion. The church activities became incorporated in the world economy and the social world of those days. Professional musicians and professional choirs played an important role in the churches. Melodies became more complicated; the language was Latin, and the congregation became spectator while the pastor became more important.

3. From the 8th Century to the 11th Century there are no sources about congregational singing. Towards the end of the Middle Ages we read for the first time about the participation of the congregation in the Mass. Church councils ordered the churches not to sing songs in any other language but Latin. But more and more songs in the regular vernacular were used (sometimes in combination with Latin, songs like: In dulci jubilo, Christ is erstanden, Nun bitten wir den heiligen Geist).

4. From the 11th Century we read about songs regularly sung by the congregation before and after the sermon in the national language. With the "Credo" the people were singing the "Kyrie Eleison". This (and other phrases) could also be spoken. All involvement of the congregation was not officially regulated but initiated by the local churches.

3. Congregational singing in the Netherlands

(In the Calvinistic Protestant Churches)

1. The earliest information about congregational singing is, that a cantor initiates a song, after which the congregation joins in. A cantor was leading the singing: often the melodies were new; there were no hymnals; many people could not read and were totally dependent on the cantor.

2. For the singing towards the end of the 16th century psalm books were used, and the singing was characterized as dignified. We read that during prosecution worship services were hold in the fields, and men became accustomed to sing very loud.

3. This way of singing was also used to distinguish from other denominations (for example Lutheran).

4. The Convention of Wezel (1568) anticipated that after the prosecution more attention for the congregational singing would be required. This convention arranged cantors in all churches, mostly school teachers, who could help the congregation with singing. Quite often the school class assisted him. This remained the practice in the churches until the 20th century.

(The task of the teacher was checked by other school teachers and organists. The children had an assigned place in front of the church and were supposed to sing very loud. There was an educational element in this arrangement for both children and congregation.)

5. The Psalm book was sung entirely from the beginning to the end. There was no relation between the songs and the sermon. This was the practice until the beginning of the 19th Century. Sometimes the congregation sung a psalm suggested by the minister. Complete psalms or large sections from psalms were sung. Individual stanzas were not sung.

6. In the 16th century people complained about the difficulty of the melodies. The introduction of all kinds of songs and hymns was an undesirable development. As a reaction, the music notes were printed for every single stanza. The children choirs, the organs and even the carillons were playing the Genevan tunes to make the people more familiar with them.

7. Early in the 17th century there were suggestions to reduce the number of melodies. The main reason for this was that psalm singing did not go very well: the singing was very slow; all notes had the same value or length (isometric singing), and there were different text versions of the psalms. Moreover, there was singing in different languages at the same time, and improvised sung interludes between the lines, and more.

8. Therefore, pro's and con's regarding a reduction of the number of melodies were heard (the well-known poet Jacob Revius was in favor of the Genevan tunes while Constantijn Huijgens and Gijsbert Voetius wanted a reduction). In several documents we read that singing in the church was unpleasant, lingering, and not understandable. Several ministers published a version of the psalm book with a reduced number of melodies. This did not solve the problem and was never generally accepted.

9. The psalm book of 1773 (Statenberijming) was a general improvement for the singing in the churches. The introduction of this new psalm book was a reason to put more emphasis on the singing in the churches. A kind of rhythm was introduced and the tempo was increased, with the result that it became understandable what was being sung. This was an important step forwards.

10. In the 19th century we find all kinds of publications about church songs and liturgy. The synod of 1817 (of the Nederlandse Hervormde Kerk) appointed a "Worship Committee" that had the task to continue to stimulate and improve the singing. In that period choirs were introduced as well, which promoted the psalm singing, and they participated on special occasions with the congregational singing in the church. In 1807 a songbook "Evangelische Gezangen" (Evangelical Hymns) were introduced, which provided a broader selection of songs, mainly for home usage.

11. Many church musicians pleaded for a reduction of psalm melodies to 20 in stead of 123 different melodies (Synod of 1870-1875). Some musicians (J.G. Bastiaans) and church historians (J.G.R. Acquoy) argued that a better notation of the original melodies would lead to better singing. Synod agreed to return to the original melodies in the original rhythm. The psalm book of the Nederlandse Hervormde Kerk of 1938 had for the first time since many years the original rhythms. However, until 1948 there was practically no real change in the singing: the old way of singing was still in use (isometric).

12. A significant change was accomplished by the musician Ina Lohr, who got her education in Amsterdam and Basel (Scola Cantorum, Switserland). Her approach was to educate musicians in the origin of the Genevan tunes, pointing out the relation with Gregorian (and Jewish) music. Singing in a faster tempo and in the correct rhythm made the Genevan tunes generally accepted in most Protestant churches. Refreshing ideas, new perceptions, original composers, conductors, and many musicians brought the congregational singing to a new level, in and outside the Protestant churches.

Note 1.

More information can be found regarding congregational singing in the different psalm books for organ accompaniment throughout the ages. The written compositions and accompaniment tell a lot about how the congregations did sing. Also positive or negative exceptions can be found.

Note 2.

The role of the organ in the accompaniment of the congregational song has widely varied throughout the ages. This subject merits a separate chapter by itself. One misunderstanding needs to be mentioned here: the fact that musical instruments were not allowed to play a role in the church liturgy, was found first in the early churches as a reaction against misuse of music in the world, and is not typical of Calvin. Also today there are Protestant churches (e.g. in the US, Scotland, and Russia) that do not allow musical instruments in the church service.